Launched in February 2006 with an urgent goal — to save U.S. soldiers from being killed by roadside bombs in Iraq — a small Pentagon agency ballooned into a bureaucratic giant fueled by that flourishing arm of the defense establishment: private contractors.

An examination by the Center for Public Integrity and McClatchy Newspapers of the Joint Improvised Explosive Device Defeat Organization revealed an agency so dominated by contractors that the ratio of contractors to government employees has reached 6-to-1.

A JIEDDO former director, Lt. Gen. Michael Oates, acknowledged that such an imbalance raised the possibility that contractors in management positions could approve proposals or payments for other contractors. Oates said the ratio needed to be reduced.

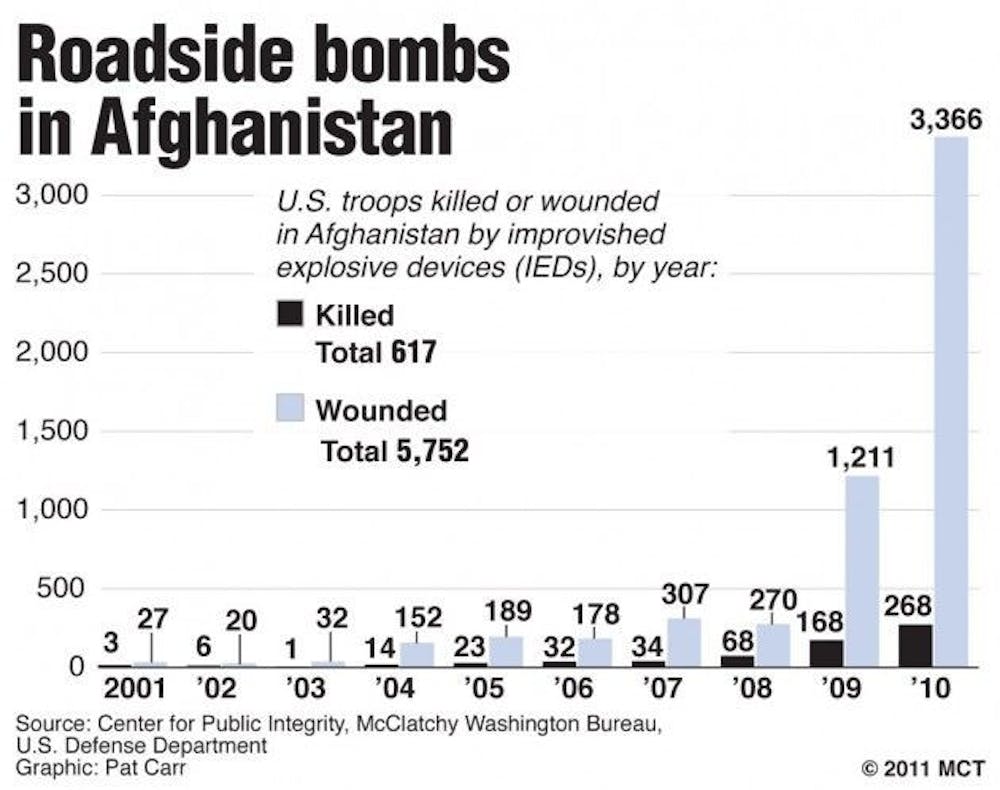

The 1,900-person agency has spent nearly $17 billion on hundreds of high-tech and low-tech initiatives and had some successes, but it's failed to significantly improve soldiers' ability to detect roadside bombs, which have become the No. 1 killer of U.S. forces in Afghanistan.

The emphasis on contractors has earned the agency criticism from government auditors and experts, who say that it hasn't properly accounted for their work. The critiques raise questions about the Pentagon's bureaucratic approach to solving a battlefield problem such as the crude, often-homemade roadside bombs that accounted for the deaths of 368 coalition troops in Afghanistan last year, according to icasualties.org, which tracks military casualties in the Afghanistan and Iraq wars.

"The number of contractors is grossly out of whack for what we would expect," said one congressional staffer who helps oversee JIEDDO but wasn't authorized to be quoted by name.

As early as 2008, the Government Accountability Office said that JIEDDO "does not fully identify, track and report all government and contractor personnel" in accordance with Defense Department rules. While Oates said the agency had since set up systems to do so, he agreed that it's long relied too heavily on private companies.

"When you get ready to spend money or make decisions with regard to the government's money, there has to be or should be a ... military or GS (government service) person who makes that decision," Oates said in an interview.

The agency's origins date to the early months of the Iraq war, when U.S. troops in Iraq suddenly found themselves under siege from roadside bombs, which the military dubbed improvised explosive devices. In the summer of 2004, Gen. John Abizaid, then the head of U.S. Central Command, sent a memo to Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld calling for a "Manhattan Project-like" effort to quash the threat.

The Army formed a 12-person task force and gave the project a $100 million budget. In 2005 the task force was turned into a joint forces team and its budget mushroomed almost overnight to $1.3 billion.

With deaths from roadside bombs spiraling out of control — from 50 in 2003 to 400 in 2005 — an even grander effort was sought the following year.

Led by Montgomery Meigs, a retired, four-star Army general, JIEDDO was endowed with nearly $3.6 billion in its first year. Word passed quickly to defense contractors, inventors, universities and government labs that JIEDDO had more than $3 billion to spend and was looking for high-tech solutions.

Contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars were awarded to major defense firms. By September 2010, JIEDDO had 110 military employees, 142 Army civilians and 1,666 contractors on board, according to the agency.

Using its own cost multiplier of $225,482 per individual, the estimated cost for contract staffers last year alone was more than $375 million.

"A lot of people were feasting off JIEDDO," said Dan Goure, a former defense official who's a vice president at the Lexington Institute, a Washington-area research center.