A white member of Sigma Phi Epsilon caused uproar amongst audience members at Pi Phi Karaoke Night on March 16 when he uttered the N-word on stage.

This incident was immediately addressed by audience members at the event and on social media, sparking a coordination of a silent protest in the University Center on March 19 condemning the usage of the term. The issue was further addressed that evening by a “Let’s Talk” session on racism and the power of the N-word and by an email sent March 20 by University of Memphis President M. David Rudd.

Regardless of the university’s attempts to address and investigate the event, the issue of racism on campus and the outrage the N-word causes has not gone away for many. Some students are still angry about what happened, and intermingled within the incident and its subsequent events are the long-debated questions of who can say the N-word, its meaning and if it should be used at all.

Shelby Crosby, professor of English and an African-American literature scholar at the U of M, said the usage of the word and the way it is perceived depends on its “context,” which can be confusing and difficult for people to understand.

“It isn’t black or white,” Crosby, who is black, said. “We want ‘either, or. Say it or don’t,’ and what’s actually developed is a contextual use of the word. So it’s dependent on what situation you’re in, who you are and what group of people you’re with. That’s way complicated.”

The occurrence and reaction of the Karaoke Night incident showed the contextualization of the N-word is a slippery slope for many. Understanding the usage of the N-word can become increasingly hard when certain rules and exceptions are applied by some to its perception, such as ending it with an “-a” to mean something less derogatory than ending it with an offensive “-er.” The issue can also become blurred by the alteration of the word’s meaning by certain people.

The N-word has its roots in Latin and early European languages as the word for black, but it did not take on the racial meaning associated with it today until the onset of slavery in 1619. There, it was used as an epithet of negro to identify and degrade slaves. Even after slavery was abolished in 1865, the racial slur was still present and publicly used in the white community in a negative fashion.

By the 1970s, the word had largely fallen out of white usage in public and became adopted by black people in music, film and satirical media, as well as in black vernacular.

Although many stances on who should say the N-word have come to light since Karaoke Night, many people think white people simply cannot say the word. Crosby said it is “shocking” when white people use the N-word, regardless of whether they end it with an “-a” or an “-er” because of its harsh background. She said the word has a “racialized power,” and when white people use the word, it calls up a historical “debasement” and stereotype of black people.

“Language is about power and how we perceive power, and I think that’s what people don’t get,” Crosby said. “When someone calls you a nigger, and they mean it, that means that you are not human to them, that you are in fact not visible, that they don’t see you for who you are. They see you for the Sambo. They see you for this being that is less than them, that is not part of the human family.”

Despite the word’s degrading past, it has come to be largely used in the black community, not in a derogatory fashion, but as a term of address or endearment. Some black people argue that this usage of the N-word is meant as a repurposing of the term away from its original meaning and into something of solely black ownership.

Crosby was unsure if the word could ever truly be reappropriated and separated from its past, even if it may “validate” the identities of some black people. Nikki Jones, associate professor in the department of African-American Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, said any word can be changed by a culture within itself even if others do not agree.

“Any word has the potential to be transformed because of the meaning that people attribute to it,” Jones, a black person, said. “Certainly there are members of the black community who don’t think you should use the word in any way at all. But to say ‘my nigga’ can be seen as a term of solidarity or a term of endearment akin to my close friend, my buddy.”

Along with its different interpretations, also adding to the N-word’s controversy is how many black people “allow” certain friends of other races, particularly white, to use the term. While some people disagree on this practice, Jones said conflict only arises when people start “policing” what others can say. She said ultimately the decision in these situations lies with those using the term with one another.

“The University of Memphis is not the only place where this kind of thing happens, and where the tension often emerges is when black people are saying directly to white people, ‘You can’t say the word,’” Jones said. “For people who are using it as a term of closeness, they get to decide who in their small social circles gets to use that word with them.”

Both Crosby and Jones said a college campus, where student bodies are diverse, is the ideal place to have conversations about this subject, especially with the U of M’s location in the South. Jones said discussing the N-word will be most beneficial when trying to resolve the issues and questions posed by the term.

“I think the conversation on the way to answering that question is more useful than the answer to those questions,” Jones said. “Language is not fixed. Culture is not fixed. It’s something we create with one another.”

With so many variables in play when contextualizing the N-word, U of M students remain divided on when and if the term should be used as well as its meaning.

Katherine Hall, a 24-year-old psychology major from Memphis, said no one should use the N-word due to its “negative connotation,” but she also said she understands any effort to reappropriate the word by black people who have “more of a stance” to say it.

“There’s too much hate associated with that word, and I think our culture would be a lot easier if it would just slip out,” Hall said. “I am white, so I’ve never had to deal with a racial slur, and I’ve never had that battle. So, it’s hard for me to say what is right for someone else to do as far as that goes.”

Accounting major Karen Huoch, a 21-year-old Cambodian from San Jose, California, said there is “no need” for the N-word to be used even by black people. She said it was “unnecessary” for black people to use it as any form of classification.

“It’s something I don’t like, but a lot of people do it, and I don’t understand the whole concept of using that word,” Huoch said. “What does it mean to say that to one another? Why do people call each other that? What’s the purpose?”

Ken Harris, an 18-year-old black journalism and music business double major from Cordova, Tennessee, said the word only belongs in “black vocabulary,” and no white person should say it under any circumstances.

“In my opinion, for black people, nigga means ‘my fellow black person,’” Harris said. “How’s a white person going to say that to another white person, let alone say it at all? White people called us the N-word for centuries, never called each other that, never wanted to call each other that either. But when we finally want to use that as a word to put in our vocabulary, all of a sudden they want to call each other that? That doesn’t make any sense to me.”

Harris said he did not agree with the idea that no one should say the N-word because black people are entitled to it. He said he did not exactly agree with those who say the word has been repurposed into something “positive” but did say there was a “slim-to-none chance” a black person would use it as a derogatory term for another black person.

“I shouldn’t lose my right to say the N-word since I was called that forever,” Harris said. “I don’t necessarily agree with some black people saying we’ve flipped the N-word around into something that brings us together in a positive way. I do believe it is something that can only be used in black lingo, and it’s one of those things a black person wouldn’t get offended by if another black person said it.”

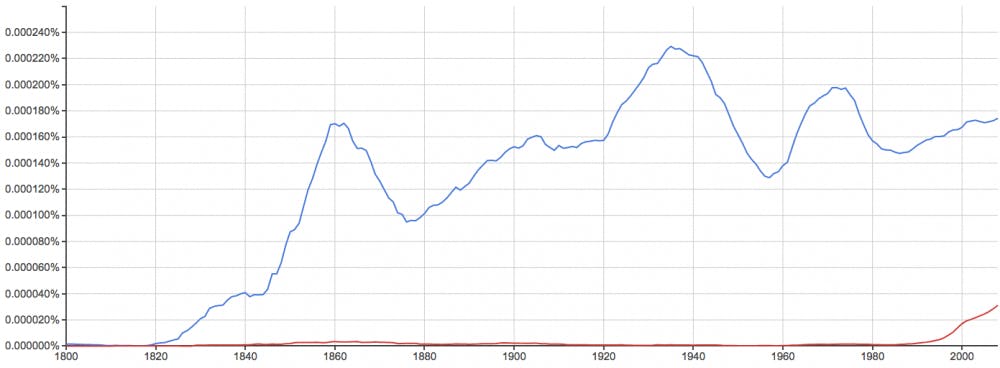

A graph from Google Ngrams shows the usage over time of "n***er" (blue line) and "n***a" (red line). Usage of both words were on the incline in 2008, the latest available data set.